Surrealism on Achill Island: the forgotten oeuvre of Sean Cullinane

The oeuvre of Sean Cullinane (1915-70), an Achill-based musician and dramaturgist, represents a rare example of an Irish Surrealist practice that was committed to the radicalism, both formal and political, of its French counterpart. Cullinane first came into contact with Surrealism through an encounter with Antonin Artaud (1896-1948) during the latter’s 1937 visit to the Aran Islands. A former seminarist, Cullinane abandoned this vocation after meeting Artaud, and under his influence pursued increasingly unconventional dramatic forms combining narrative and musical contents. As the son of a postmaster, Cullinane had facility in languages and opportunity to correspond with Surrealists internationally. In 1939 he compiled and illustrated a compendium of psychoanalytic renderings of and poetry based on local folklore, which he delivered to French poet and theorist André Breton (1896-1966), the de facto leader of the Surrealist group, in a failed attempt to gain recognition for an Irish contribution to the international Surrealist movement. This manuscript was unknown until Breton’s estate came to auction in 2003. The primary sources of information concerning Cullinane’s initial turn to Surrealism come from family records and a diary Artaud wrote retrospectively in 1944, which has recently been disembargoed by his estate. Little of Cullinane’s work survives: following Artaud’s advice to eschew the use of written texts in the theatre, the majority of his performances and pieces were executed without scores or textual support. His notorious productions were, however, well remembered by local people, and the recent discovery of extracts from a radio play produced by Cullinane makes it timely to consider what can be reconstructed of his oeuvre. Cullinane’s radical Surrealism has resisted both contemporary and historical institutionalisation, existing instead in close relation to the land, people and traditions of the rural island, and offering an anarchic contrast to the more staid responses to Surrealism current in 1930s Dublin which have since dominated discussions of Irish Surrealism.

Early Life

Cullinane’s life and practice have been difficult to reconstruct, given the almost total lack of textual material that he left behind. Cullinane was born in the spring of 1915 to Edward Cullinane, a postmaster on the Currane peninsula, and his wife Margaret. He was the second of four children and their second son. The family had benefited from the activities of the Congested District Boards, and their relatively comfortable position was consolidated by Cullinane senior’s position as a postmaster: he had a degree of literacy in multiple languages, and the post office’s integral role in connecting Currane to the mainland proper ensured steady income for the family. Perhaps as a consequence of this stability Edward Cullinane seems to have had limited and conservative political interests. Cullinane’s family could, therefore, be described as belonging to an indigenous petit-bourgeois that was emergent in early twentieth-century Ireland.

Accordingly, Cullinane was well educated, being schooled at the Franciscan monastery in Bunacurry (during which time he boarded with the family of his father’s cousin on Achill), and later at Rice College, a Christian Brothers’ institution in Westport. At school he excelled in languages and religious studies, serving diligently at mass first as a chorister and later as a sacristan. He had, however, no aptitude for mathematics, which would preclude him from succeeding in civil service entry examinations as his father had intended. Cullinane was instead sent to a formation house in Dublin, where he hoped to pursue a degree in philosophy alongside his seminarial studies. Information concerning Cullinane’s life in Dublin is scant. He is recorded as participating in the 31st International Eucharistic Congress held in Dublin in 1932. He sent a postcard to his sister Nora from New Grange in 1935, after having been invited to observe an archaeological expedition by a Trinity student named Brian Carroll. Cullinane described the “strange and startling” impact that his visit to the site had on him. He wrote of the “unsettling low mound, at the one time both repelling the outsider from penetrating the mysteries within, and inviting us into the passage by lure. I hear the sight of the sun in the hall at the death of the year is nothing short of the splendour of a resurrection.”

This card seems to be the final record of Cullinane’s life in Dublin. By 1936, he was still not ordained and was now living on Achill Island. It is unclear what affected this change of circumstance: Cullinane’s sister recalls that he originally went to Achill with the intention of making a short religious retreat, but in retrospect it seems that this retreat was motivated by vocational doubts that Cullinane was already, by this date, experiencing. He requisitioned a cottage in Slievemore on the north of the island, adding to the existing “four mostly sound walls” a roof of sheet tin. Slievemore had been the main site of a Church of Ireland mission to ‘civilize’ the population of Achill, led by the Reverend Edward Nangle (1800-83) between 1834 and the 1880s. Nangle’s practice of distributing food aid to families willing to convert to Protestantism at the start of the Great Famine in 1831, and his success in becoming landlord of much of the island, has ensured that he remains a controversial figure in the history of Achill.

Nangle’s activities, his perceptions of Achill and his descriptions of what he felt to be persecution by Catholic resistance on the island were well documented by the publishing and distribution activities of his own corporation, the Achill Press. Cullinane read as many outputs from the press as he could obtain, including issues of the Achill Missionary Herald and Western Witness. These texts, though authored from a position of clear religious bias and with the intent of raising subscriptions for Nangle’s colonies, nonetheless contain some potentially enlightening information concerning the lifestyles and religious practices of the population of the island in the later nineteenth century. The populace Nangle found was deeply superstitious, and able reconcile faithful adherence to the tenets of Catholicism with strongly-held supernatural beliefs without any apparent difficulty. Of course, for Nangle, a belief in the supernatural was no less superstitious than a belief in what he termed the ‘Popish idolatry’ of the Catholic church. His initial lack of knowledge of Irish led him to underestimate educational levels on the island, while his ambitions for the growth of his mission allegedly encouraged some disingenuity in his understatement of the depth of commitment to Christianity. He described Achill as both “temporally and spiritually” destitute, and in urgent need of the intervention of formal religion. Rumours circulated that he had deliberately overestimated the population of the island, and had fabricated claims that the residents had never heard of Christ and instead worshipped a large glassy stone embedded into the side of Slievemore mountain. Though Nangle disputed that he had made such false claims, he was nonetheless derided for his “calumniation” of Achill. His own writings made ad hominem attacks on his detractors, “gentlemen [who] do not enjoy the luxury of shoes and stockings, except on Sundays and holydays; few of them know how to read, fewer still can write their names.” Yet however problematic, it would be Nangle’s writings as much as his own direct experiences that formed Cullinane’s perception of the island. While Nangle’s political and religious agendas were anathema to Cullinane, Nangle’s ideas on the spiritual life of the people shaped Cullinane’s conviction that both the population of the island and the island itself existed in an unusually close communion with the supernatural, a belief which would determine his intellectual interests and the concerns of his artistic practice.

Nangle had primarily been active in Slievemore but had formed a smaller mission at Mweelin, near Dooega village, and these sites also became Cullinane’s locales; he would regularly walk the seven miles between the two villages. In addition to his admiration for the natural features of the island, Cullinane enjoyed visiting neolithic sites, including the Cromlech tumulus, a court tomb on the route. His encounter with this small megalithic structure was formative: having heard a local legend that the mound housed a bain sidhe (or banshee, a female psychopomp in Celtic mythology) Cullinane was drawn to the site, and inspired to begin keeping a notebook of Achill folklore. He interviewed friends and family in Slievemore, Sraheens and Dooega, providing particularly florid detail of those stories with supernatural elements. While Nangle had aspired to eradicate folk superstitions, Cullinane worked in opposition to any attempt to normalise the spiritual life of Achill by codifying what he regarded as its mystical patrimony, documenting whatever evidence of the “living will there is amongst us towards those elements of the spiritual which must remain to man mysterious” he could find. Cullinane took a sensitive approach to this material, displaying a cultural relativism that was advanced for someone in his position during this period. Through this work and his series of interviews Cullinane acquired a reputation as a scholar, and though his interest in local traditions was thought by some to be peculiar, the sincerity he displayed in his endeavours led to him being generally well-liked on the island.

It was his repute as an earnest and engaged student of Achill customs that brought Cullinane into contact with the French dramatist Antonin Artaud. In 1937 Artaud arrived on the islands off the West coast of Ireland, seeking to recreate JM Synge’s (1871-1909) visits to Aran between 1898 and 1902. Synge had himself travelled there in search of the pre-Christian Pagan worldview he believed to have been retained by the rural Irish peasantry. Artaud had previously visited Mexico, where he developed an interest in ancient religious systems and “cosmogenies”. His concern for pre-Christian religions was consistent with Surrealism’s mistrust of the dominant influence of ancient Rome on European patrimony, an expression of the suspicion of teleological historical narratives that the Surrealists held in common with other post-WWI avant-gardes. However, where the majority of these avant-garde movements sought a radical break with established historical, cultural and artistic conventions, the Surrealists attempted to position their production within an alternative cultural history, tracing transhistorical and transnational precedents for their work. Across the corpus of Breton’s writings this lineage becomes extremely wide-reaching and comprehensive: it included Irish writers he admired, such as Jonathan Swift and Charles Maturin, and stretched back as far as ancient Gaul. It was in this spirit of lineage-tracing that Artaud sought to correct “the false conceptions the Occident has somehow formed concerning paganism and certain natural religions, and [to] underline with burning emotion the splendour and forever immediate poetry of the old metaphysical sources on which these religions are built.”

Contemporary correspondence detailing Artaud’s itinerary, misadventures, and the international controversy which these generated remains extant, excerpts from which were reprinted in the first issue of The Dublin Review. He arrived at Cobh on August 14th, later going to Inismor until September 2nd. He travelled onward to Dublin on September 8th, from where he was deported on September 14th. A period of six days, between September 2nd and 8th, have previously been left unaccounted for. A recently disembargoed 1944 diary by Artaud describes a visit to Achill and his meeting with Cullinane during this period. Artaud recounts a meeting on Inismor with Dr King, a medical practitioner who serviced several of the islands off the West coast. King, who had studied French, was curious to meet the visitor, and during their conversation Artaud informed King of the purpose of his trip to Ireland: he was acting on a self-appointed mission to plant an elaborate walking staff he was bearing into the base of Croagh Patrick, a mountain in Mayo which has been a site of pagan and later Christian pilgrimage for around five thousand years. Achill being considerably closer to Croagh Patrick than Inismor, King offered to take Artaud with him on his return journey, and recommended that he meet there a priest with intimate knowledge of ancient mythology, whom King believed would be the best placed companion for his mission.

In his haste to depart Artaud left behind him an unpaid debt which ignited a small diplomatic incident. On September 4th King introduced Artaud to Cullinane and the three had a brief conversation in French. On September 5th the two men travelled together by road to the Croagh. Acting on the basis of apocrypha which describe St Patrick striking a walking staff into the ground and it growing into a living plant, Artaud plunged the staff into the mountainside in the belief he was achieving a symbolic union of male and female archetypes, a gesture which held for him both cosmological and sexual significance. The next event he recalls was on September 8th when, for reasons that were opaque to Artaud, he was taken by the priest to the station at Westport and boarded onto a train for Dublin. The priest funded his journey and urged him to return home to France. Cullinane seems to have feared Artaud’s obviously degenerating mental health (he was ultimately expelled from Ireland and sectioned on his arrival in France). On arriving in Dublin Artaud had no recollection of these events and reported his staff missing to Dublin constabulary, but was nonetheless able to describe his visit to Achill in some detail in his 1944 memoir, which was written towards the end of his life and whilst receiving electroshock treatment under Dr Gaston Ferdière in Vichy France. The circumstances in which Artaud wrote the memoir were no doubt trying, and at the time it was undertaken he was being actively encouraged to examine his memories and express himself creatively as part of his therapeutic program. Though there is no way of verifying the details Artaud gives, the strong influence of Artaud’s theories is borne by Cullinane’s later works.

Departure from the Church and Early Work

Despite his apparent concern over Artaud’s conduct on Achill, Cullinane remained deeply affected by the encounter. He is recorded as having officially departed from his seminary in September 1937. After meeting Artaud he made effort to order and read his publications, depending on the post office at Dooega for receipt of information about contemporary Paris. Though Artaud had broken from Surrealism by the time of his meeting with Cullinane, having disagreed with Breton’s 1927 affiliation of Surrealism to Communism, he remained a conduit of its influence; the texts by Artaud which Cullinane could immediately access were those which appeared in Surrealist journals, as Artaud would not publish his magnum opus, Le Théâtre et Son Double (The Theatre and Its Double, 1938), until the year following his departure from Ireland. Artaud’s most influential idea, his conception of the ‘Theatre of Cruelty’, was developed over an extended period between 1921 and 1938: Cullinane’s remaining work seems closest to the later conception articulated in Artaud’s Second Manifesto of the Theatre of Cruelty (1933). While the first manifesto derided the “servitude to psychology and ‘human interest’” of realist theatre, in the 1933 text he clarified that this did not preclude investigation of “subjects and themes corresponding to the agitation and unrest characteristic of our epoch”, as his proposed theatre did “not intend to leave the task of distributing the Myths of man and modern life entirely to the movies.” Cullinane first read these manifestos in the Theatre and Its Double, which he obtained soon after its publication. In the interim he managed to acquire, amongst other texts, the first three issues of La Révolution Surréaliste (The Surrealist Revolution), to which Artaud had contributed important texts on world religions. Artaud’s influence seems, however, to have primarily been exerted by means of direct contact between the two men: it was only weeks after meeting Artaud that Cullinane would perform his best-remembered work, in response not only to their meeting but also to highly emotive events which impacted the Achill community and had repercussions throughout the British Isles.

Kirkintilloch

Cullinane had in the course of his researches into the folklore of Achill encountered the sayings of Brian Rua O’Cearbhain, a seventeenth-century Mayo mystic known as the ‘Prophet of Erris’. No contemporary record of O’Cearbhain’s prophecies exists, but one particularly concerning Achill has entered into folk memory: O’Cearbhain foresaw ‘fire-powered carriages on iron wheels’ connecting the mainland to the island, the first and last of which would ‘bring death’ with them. The first part of the prophesy was fulfilled in 1894, when thirty-two migrant workers from Achill drowned in Clew Bay, on route to agricultural jobs in Scotland. The first service to run on the line, which at this point remained under construction, brought their bodies home for burial in Kildownet cemetery. The line was scheduled for closure due to lack of demand for the service, and the last passenger trains ran in 1936. It seemed the second part of the prophecy had been circumvented. However, freight services continued to run, and before the line’s ultimate closure it received a cargo of bodies into the island in what would be its final service.

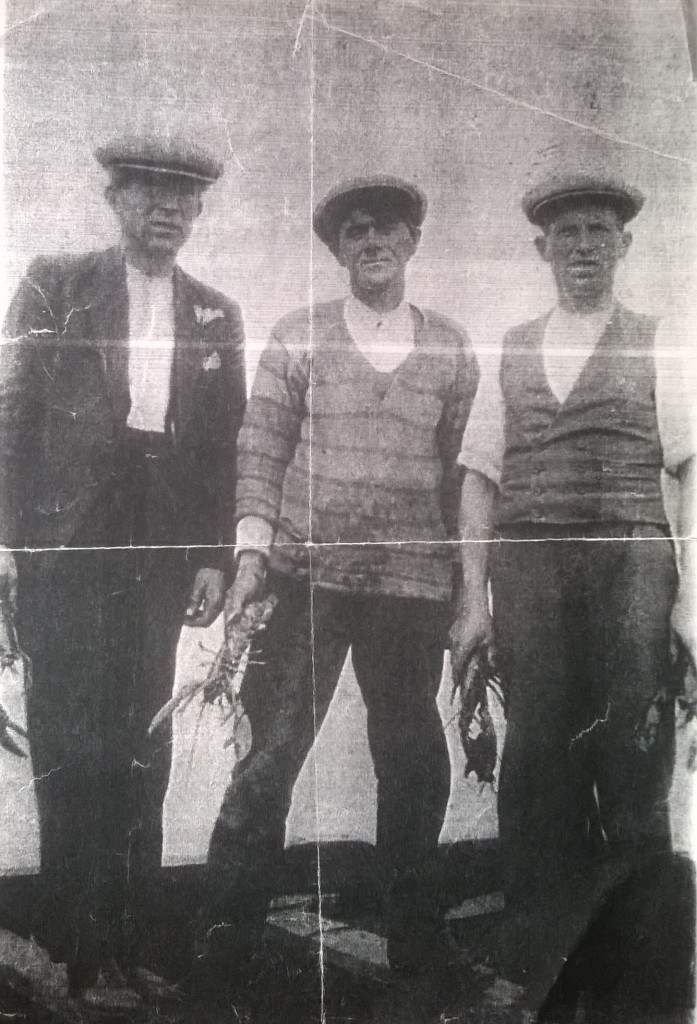

On September 15th, 1937 twelve men and fourteen young women from Achill arrived in Kirkintilloch, Scotland, to take up short-term agricultural employment. By the following morning ten of the young boys, who had been sleeping in a ‘bothy’, a poorly-furnished outbuilding, were dead. Overnight a fire had broken out in their quarters, and as the building had been locked from the outside the boys, who ranged in age from 13 to 23, were unable to escape. The tragedy had far-reaching international consequences, sparking parliamentary reform of conditions for agricultural and migrant workers. Barry Sheppard’s well-informed account of the tragedy and the response describes a “particularly sharp outpouring of grief” across the British Isles. A service was held for the boys in Kirkintilloch, attended by around three thousand mourners and British and Irish dignitaries. After arrival in Dublin, where a service was also held, a special train service took the coffins to Achill for internment. The train was greeted by a large congregation of mourners, and around half the island’s population participated in memorial events. Some remember a train entering the island immediately proceeding the coffin train, in which they saw spectors of their deceased relatives seated in passenger carriages as if they were still alive. Despite the ramifications, little is known about how the tragedy itself unfolded. The most elaborate accounts describe the girls in the party helplessly witnessing the engulfment of their trapped brothers through the windows of the bothy; the impediment of rescue and fire services through these witnesses’ inability to speak in English; and the presence of a Catholic priest on site, administering the Last Rites. It seems unlikely that the blaze would have progressed sufficiently slowly for these events to have occurred, but rapidly enough to prevent the rescue of the boys. Irrespective of their veracity, however, such news reports would have made deep impression on contemporary readers and particularly on surviving family.

Cullinane was profoundly affected; he had himself cousins on Achill who worked under similar conditions. He turned to theatrical expression to process his and his neighbours’ feelings on the tragedy, apparently following Artaud’s assertion that the most serious and affecting contemporary events were not only appropriate subjects for theatre, but precisely what theatre should address itself to in order to fulfil its social and psychic utility:

“great social upheavals, conflicts between peoples and races, natural forces, interventions of chance, and the magnetism of fatality will manifest themselves either indirectly, in the movement and gestures of characters enlarged to the statures of gods, heroes, or monsters, in mythical dimensions, or directly, in material forms obtained by new scientific means.”

Thus Kirkintilloch became the subject of Cullinane’s most sustained and emotive output. Artaud’s strong prohibition against “act[ing] a written play” informed Cullinane’s improvised approach: he worked with collaborators, including amateur actors and musicians, who generated vocals and dialogue around a set scenario devised and directed by Cullinane. While the performances were not spontaneous – by the time they reached audiences the improvised elements had been codified through extensive rehearsal – this working process does mean that no scripts survive. Performance art represents a challenge to cultural historians, who must reconstruct stagings on the partial basis of documents and ephemera. This is further complicated in the case of Cullinane’s response to Kirkintilloch, which seems to have been performed in more than one version, both for live audiences and for recording, and under different titles. However, one participant in his performances, Martha O’Mally, has described her recollections of his work. O’Mally, who was training to become an Irish teacher in Tuam, spent time at Scoil Acla in order to perfect her language skills. She first met Cullinane in late summer of 1936 at a reading of his poetry. She described this work as a particularly gruesome (though stylistically conventional) thirty-seven verse narrative about a man entering a Faustian pact with a fish, gaining omniscience in exchange for his mortal remains. The poem synthesised the legend of Fintan and the salmon of knowledge with the death a few years prior of a local man who had been blown from the perilous cliffs of the Atlantic Drive: after several days of searching, neighbours found his eyeless corpse washed up on the beach. This performance was extremely poorly received; even those members of the audience that could withstand its content did not have the stamina to stay for the complete cycle of verses. Despite its failure, the poem indicates that Cullinane was already interested in forging narratives from a meeting of myth and contemporary events, and investigating the intersection of trauma and performance. It was through Artaud’s influence that the presentation of these ideas would be refined.

Cullinane first presented his Kirkintilloch performance on October 31st. O’Mally recalls that, in his notes, Cullinane referred to the play by the rather uncompromising title Garçons condamnés à carboniser (“Boys Condemned to Burn”), but titled it Lament in the handbills he distributed on Achill. The performance centred around the myth of the bain sidhe, presented as a female ancestor spirit who returns to the world of the living at times of bereavement in order to mourn the deceased in a highly vocal, hysterical outpouring of grief. The Surrealists drew on the trope of unrestrained femininity as an antidote to the rational masculinity of European culture which had, they believed, made the First World War inevitable. Their highly problematic description of femininity as sexualised, mystical and subversive, most notably manifested in their celebrations of hysteria, informed Cullinane’s treatment of the bain sidhe. Cullinane had been interested in this figure since his first visits to the Cromlech tumulus, and chose to revisit this theme not only for its funerary connotations, but also for its explicit evocation of the bereaved woman. While the deceased of Kirkintilloch had been thoroughly memorialised through a series of services across Britain and Ireland, Cullinane was concerned that no ceremony had yet acknowledged the suffering of the surviving witnesses, the young girls who had become vessels for the ongoing psychological suffering of their community. His play, then, was intended as catharsis for what he called these “living bain sidhe”. Drawing on accounts of the presence of a priest on the night of the fire, Cullinane presents a dialogue between the formalised consolations of the Church and the unmediated emotional response of the bain sidhe, taking the role of the priest for himself; his concern for mental or spiritual well-being in the aftermath of trauma revealed his lingering desire to ministrate, and his purposeful staging of the performance on All Hallows’ Eve enforces the quasi-ecclesiastical aspects of his commemoration service for a suffering that had so far been overlooked. For Cullinane, organised religion was, despite its limitations, well-intentioned: it is notable that he never rejected Catholicism even after abandoning his vocation and applying himself to the study of paganism, a reconciliation consistent with the Achill character as he understood it.

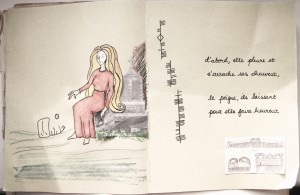

Cullinane’s conception of the bain sidhe was also specific to Achill, featuring deviations from the myth as it has become standard in Ireland. Despite the lack of textual support for the performance, details concerning his understanding of the bain sidhe are contained in an extraordinary illustrated manuscript of psychoanalytic readings of folklore that he prepared for delivery to Breton in 1939. One spread from this book shows her alongside an ogham inscription, which Cullinane may have apprised from extant engravings on Achill, and an early example of experimentation with ancient script as a way of circumnavigating Ireland’s recent linguistic patrimony: it is possible that Cullinane found his own status as a native English speaker politically problematic. That ogham functions as a syllabary, and is not unlike musical notation, may also have appealed to Cullinane. His bain sidhe is not a fairy who acts as a professional mourner for prominent families; instead, she is a specifically matriarchal ancestor spirit, who follows and mourns her descendants in the female line. She has a direct genetic relationship with those to whom she appears. The bain sidhe is most often experienced aurally: she will cry on the death of one of her children, in a voice that is only audible to the children that survive. Most unnervingly, she adopts the exact voice of the recently deceased to vocalise her grief. In a departure from the immediacy of Artaud, Cullinane does not accept the magical occurrences he describes on their own terms, but instead subjects them to a psychoanalytic treatment, presumably to appeal to the more epistemological concerns of Breton. The myth was ripe for psychoanalytic exploration: Cullinane describes her as a personification of hysteria, as a collective hallucination, and connects the fantasy of her existence to the frustrated attachments of what Freud termed the ‘family romance’, a child’s overwhelming desire for the affection of their parents and perception of them as preternatural beings. Cullinane’s knowledge of psychoanalysis was itself heavily informed by Breton and limited to what he had read in Surrealist journals, as there was scant practice of or information about psychoanalysis in Ireland at that time; indeed, the first Irish Psychoanalytic association would not form until 1942.

In his use of performance as catharsis; adoption of a real, recent and emotive event as a point of disembarkation; and recourse to mythic narrative, Cullinane realised long-held interests under the guidance of Artaud’s influence. Avoiding the use of conventional theatres in favour of performing in “some hangar or barn” was the most easily achievable of Artaud’s dictats: Achill had no theatres or non-ecclesiastical spaces large enough to be used for theatrical purposes. Instead, Cullinane held his performance on the hill slope behind the Cromlech tumulus. He and the performers stood in front of the stones, with the hillside forming raked seating for the audience. Both performers and audience were encircled by a ring of torch bearers, lighting the action and further enforcing the proximity of performers and viewers. Cullinane craved audience interaction, whether solicited (in the case of O’Mally and other participants, who were recruited from his audiences to collaborate on future works) or in the form of spontaneous interventions during the performance (though Cullinane seems to have desired this, O’Mally could not recall any unexpected contributions in the pieces she performed). O’Mally remembers being surprised by the turnout of around fifty people. Cullinane endeavoured to treat the subject sensitively, and by dealing with an important event in a way that gave serious accord to folklore and through consultation of local residents, he enabled the play to be well-received. Though some residents, including the family O’Mally boarded with (who had not seen the play) regarded Cullinane as “‘cracked’”, many were interested in his productions. The restricted availability of entertainments on Achill was also surely a contributing factor. While many artists of renown had exploited the landscape and atmosphere of the island for their work, including Paul Henry, Robert Henri and Graham Greene, this did not contribute to the development of any institutional culture on Achill. While this lack of conventional precedent gave Cullinane the latitude to execute his experiments, this also meant much of the formal radicalism of his work was lost on his audience: indeed, there was no reason for his audience to understand his recourse to ancient myth as a progressive, rather than retrogressive, intervention, indicating the difficulty of applying Artaud’s anti-institutional attack in the Achill context.

Class and collaboration

The socio-economic conditions of Achill would not only reconfigure the significance of an Artaudian theatre, but also determine Cullinane’s career. The continued economic dependence on Britain that the Achill emigrations represented was a small example of the serious poverty that blighted rural areas of the independent Irish state. This troubled Cullinane, his Catholic sympathies intersecting with what he had read about Marxism within Surrealist journals, and what he had learned of the threat of totalitarian politics throughout Europe via news of the death of Dooega’s Tommy Patten, the first Irish volunteer to the Spanish Civil War, in December 1936. Cullinane’s own feelings on the Kirkintilloch tragedy and the end of the railway were not unmixed: while the ill-fated line’s closure on September 30th was met mostly with relief by a disturbed populace, Cullinane feared the increasing economic and cultural isolation of the island. He was invited to join the Anti-Emigration and Industrial Development Committee, convened after the disaster, specifically to address these questions.

The Committee advocated the reopening of the railway line for the benefit of local industry. However, both a lack of concern at the national level and local aversion to the railway were significant obstacles. Cullinane agreed to re-stage his play for radio, primarily to publicise the plight of the islanders to the rest of the country, but also to exorcise any perceived curse on the railway. The upsetting title by which he privately referred to the 1937 play spoke violently against systems of migrant labour, and for the performance’s final incarnation on radio he gave it the title Iron Rod, a blend of direct reference to the Irish language term for railway, allusion to the national significance of the rail network, and oblique critique of the unforgiving demands and human costs of capitalism.

The play was broadcast on Radio Eireann in late 1938: with the opening of the Athlone transmitter in 1932, parts of rural Ireland, including Achill, received domestic radio broadcasts for the first time, establishing a national radio network. In contrast to the unrestrained emotion and expression of the first staging, the radio play was altogether more structured. In order to maintain the application of Artaud’s principles, one section of the play was recorded with a live audience, though this is not included in the six excerpts from the recording which have been reconstructed here. These reconstructions take as their starting point low-quality fragments of the original recordings which have survived, with additional input from O’Mally, who performed in the original piece, to supply missing details where necessary. Also missing are the narrative and dialogue sections that linked the musical sections and which, unexpectedly, adopted an accessible style bordering on social realism, and described the island as doubly-disadvantaged by both the disasters and its subsequent isolation. This combination of explicatory prose and lyrical sections is not unlike the structure of early Irish legends, on which Cullinane drew for his textual contents.

Excerpt 1 – Gach-from-Iron-Rod

The first extant section is based on the so-called Alphabet of Cuigne Maic Emoin, a collection of legal maxims and moral proverbs contained within The Great Book of Lecan, a compendium of ancient texts transcribed by Ádhamh Ó Cuirnín, a poet and scribe from Connacht, in the early 15th century. The litanous text lends itself to Cullinane’s emphatic, rhythmic treatment. The authoritative, at times dispassionate reading of the main vocalist contrasts with high pitched accompanying voices. Is Cullinane juxtaposing the measure of law against the urgent cries of the deceased, in a critique of the lack of sufficient regulation to prevent the Kirkintilloch fire? Cullinane’s adaptation of legislative proscripts to performance is consistent with oral and performative traditions of law in Ireland: that an effective leader must be a skilled orator is the assumption of Mac Emoin’s manuscript. Thus Cullinane both sets the political context of the play, reworking it into an appeal for just and responsive government, and aligns his role, as a playwrite positioned within a political campaign group, to a tradition of political persuasion or ‘Kingly speech’. This section was almost certainly devised specifically for the radio, and was not included in his Achill performance.

Excerpt 2 – Soldier-from-Iron-Rod

Excerpt 3 – Birthdays-from-iron-Rod

“Birthdays” (excerpt 3) is the first piece known to have been presented on Achill. The text describes how fortune is determined by an individual’s day of birth: “He who is born on Tuesday, drowning will carry him off, great will be his wealth in small cattle, his power will not be strong”, “many will mourn someone born on a Monday”. Each refrain opens with a description of the child’s death, a blunt acknowledgement of the inevitability of mortality. Again, rather than write a play, Cullinane adapts an ancient prophetic text in a manner of which Artaud would have approved.

Excerpt 4 – Nach-Bhfuil-from-Iron-Rod

Excerpt 5 – Lament-from-Iron-Rod

Excerpt 6 – Invocation-to-Bran-from-Iron-Rod

The next musical passage is rhythmic and non verbal, evoking the movement of a train (excerpt 4). It is followed by “Lament” (excerpt 5), which has vocal content describing psychoanalysis interspersed with incantations to a solar god. With its trailing female vocal, this was the centrepiece of the first Achill performance. It was immediately followed by “Invocation to Bran” (section 6), the penultimate musical section of the play, which describes Bran Maic Febail, an important and complex figure in several Celtic mythologies. Amongst the corpus of stories concerning Bran is one detailing his origins as the child of a union between the god of the sea and the god of the sun (it is worth remembering here that O’Cearbhain’s prophesy was fulfilled through tragedies caused by drowning and fire). Bran is also known as a god of regeneration, and there are myths concerning his attempt to journey to the Otherworld: Bran falls asleep while listening to a goddess from the Otherworld sing of the mystical island in the west from which she came, and she compels him to seek it out. The undoubtedly sexual allure of this highly vocal goddess of the Otherworld again underlines Cullinane’s conception of the bain sidhe as a signifier for a transfixing femininity. The text Cullinane adopts is a section of the Immram Brain (Voyage of Bran) which describes his visit to this Otherworld, which he finds populated by “a troop of hundreds of women” and deems “a great find for any man who could find it.” What Freud proposed as the two primary motivations of human behaviour, the sexual impulses of the erotic drive (which he termed Eros), and the will for death (Thanatos), are reconciled in Cullinane’s treatment. The hope for regeneration represented by Bran’s mediation of the Otherworld and the land of the living, and the tantalising possibility of journeying to a wonderful island, become in this rendition very obvious metaphors for Cullinane’s political campaign.

Unusually, Cullinane eschews the use of instruments throughout these surviving interludes. He was himself most comfortable as a vocalist (though he was also able to play the organ and the violin), and constructs these pieces entirely from vocals and harmonisations supported by improvised percussive sections. These are most apparent in the final section of the play (excerpt 2), where humming generates the melody, and clapping the percussion, enriched by apparently spontaneous vocal outbursts. This short section was a response to Radio Athlone’s request that Cullinane provide a concluding piece of music for broadcast before the call sign. In contrast to the other excerpts, it is upbeat and implicitly evokes the national anthem, the Soldier’s Song: through reference to Ireland’s new status as an independent nation, Cullinane reiterates his case for the need of an intergrating national infrastructure.

Throughout these musical sections the actor is treated as a “living instrument”, with gesture, dialogue and vocals integrated into a continuous presentation. Artaud advocated the incorporation of music in theatrical performance, especially through the use of “sounds or noises that are unbearably piercing”, which seems to bear a strong influence on those sections of the recording that survive. The execution was startling, with shifts in tone and expression exploiting a full vocal range. The anti-naturalistic, distorted vocals use words in “an incantational, truly magical sense”, “experienced directly by the mind without the deformations of language and the barrier of speech.” The arbitrary, nasal vocal style Cullinane directed also bore some resemblance to sean nós, which may represent a hybridisation of Surrealist and indigenous precedents. However, it is also possible that the influence of Irish cultural forms on the development of Artaud’s ideas has been under-recognised: he deliberately followed Synge to Aran, where he could have experienced folk performance at first hand, and did not make his first book-length publication of theatrical theories until after his return from Ireland to France.

Correspondence with Breton

Though his local reputation was secured by these efforts, Cullinane never enjoyed much national or international recognition. It has been suggested that post-revolutionary Ireland did not offer the right cultural or political conditions for the development of Surrealism, and there is a degree of irony in this assessment given the Parisian Surrealists’ sympathy for post-colonial struggles, which saw them lend support to regions where revolution was in progress, including Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia. Ireland offered an example of a stable post-revolutionary state within the Surrealists’ European cultural context. In the 1929 Surrealist Map of the World Ireland looms large, subsuming a post-colonial England which has dwindled in geopolitical importance. However, the revolutionary utopia represented by Ireland was not only metaphoric, but also literal. The 1939 outbreak of WWII saw an exodus of liberal artistic talent from the UK to Ireland, exerting transformative influence on Irish modernism. The artists Kenneth Hall (1913-46) and Basil Rakoczi (1908-79), who would go on to form the White Stag group, brought with them from England a post-Surrealist interest in psychoanalysis, politics and sexuality. The Stags and their dissemination of a Surrealist influence through Dublin’s Exhibitions of Living Art (which painter Mainie Jellet (1897-1944), a regular visitor to Achill, co-founded in 1943) have dominated discussions of Surrealist influence on Irish art, despite the fact that scholars describing their works remain justifiably cautious in designating their work ‘Surrealist’. Certainly the Stags were attempting to formulate an advance on Surrealism, by retaining is social and psychic contents, but reinstating aesthetic concerns. Though it is unfair to call this “watered-down Surrealism”, their paintings can be unfavourably compared to Cullinane’s earlier and more ambitious provocations.

The fact that Cullinane left little material contributes to his having been, in comparison to the Stags, overlooked. The emergency, which fostered the work of the Stags, curtailed Cullinane’s artistic output and his work with the Anti-Immigration and Industrial Development Committee. Instead, Cullinane turned his attention to international developments. Like many Surrealists outside France, he wanted to position his work within the international Surrealist movement through correspondence with Breton. That Cullinane privately referred to his Kirkintilloch play by a French title suggests he formed the idea of presenting work in France very soon after his encounter with Artaud, but he would not send material to Breton until 1940. Breton was primed by his interest in Celtic material culture, especially Gallic art, which he first wrote on in Surrealism and Painting (1930), and argued offered artistic precedents untainted by Roman or Christian influence. As his own family originated in Brittany, his interest in Celtic forms was highly personal. Cullinane does not articulate any anxiety over melding a movement imported from modern France to his own indigenous culture, possibly as a result of the Surrealists’ favourable assessment of Ireland. However, Breton seems not to have received Cullinane’s work with much enthusiasm, and seems never to have written on any contemporary Irish artist; his interest was exclusively in Ireland’s ancient patrimony, which he fetishised in the same manner as he did the cultures of revolutionising states outside Europe (and which was possibly encouraged by his own reading of Synge). For Cullinane, too, Achill provided an extensive repository of fertile tropes but did not offer the contemporary cultural environment necessary to sustain avant-garde experimentation. Though he never encountered the extreme condemnation with which other avant-garde interventions, such as those of Chancey Briggs, were met, the radicalism of his theatrical forms was drastically curtailed by the lack of any institutionalised theatre on this island. Cullinane was also disheartened by his failure to find any national audience. Breton’s lack of interest did not, however, dissuade Cullinane from going to France after the war. He was deeply affected by Artaud’s 1948 death, which he learnt of shortly after his arrival in Paris, as he was hopeful that he would eventually be discharged from psychiatric care and that they could resume their exchange. Cullinane had some contact with the Parisian group, and contributed to their enthusiastic support of the Prague spring of 1968. He died later that year, leaving behind only some ephemera, a fragment of recording, and a single manuscript.

Select Bibliography

“An absent-minded person of the student type”: Extracts from the Artaud file”, The Dublin Review, Issue 1, Winter 2000-1, available at http://thedublinreview.com/extracts-from-the-artaud-file/, accessed August 31st, 2014.

Antonin Artaud, The Theatre and Its Double, Mary Caroline Richard, trans., Grove Winfield, New York, 1958.

Cyril Barrett, “Irish Nationalism and Art II: 1900-1970”, Studies: An Irish Quarterly Review, vol 91, no 363, Autumn 2002, pp223-38.

André Breton, “Second Manifesto of Surrealism” (1930), Richard Seavers and Helen Lane, trans, Manifestoes of Surrealism, Ann Arbor, 1969.

Oeuvres Complètes, Gallimard.

College of Psychoanalysts in Ireland, “A Brief History of Psychoanalysis in Ireland”, available at http://www.psychoanalysis.ie/about/history/, accessed October 1st 2014.

Brian Fallon, “The White Stags”, Irish Arts Review, vol 22, no 2, Summer 2005, pp68-73.

Peter Gay, ed., The Freud Reader, Vintage, 1995

SC Hall, Ireland: Its Scenery, Character and People, How and Parsons, 1843.

Roisin Kennedy, “The Surreal in Irish Art”, available at http://www.femcwilliam.com/News/Surreal-in-Irish-Art-exhibition-now-open.aspx, accessed 11th December 2012.

La Révolution Surréaliste

Terese McDonald, Maeve McNamara, Caoline Cowley, Emma Dever, Thomas Johnstone and Hessel Van Goor, “Achill’s Railway Station – In History and Story”, available at http://www.eu-train.net/connect/story/stories/achill_railway.htm, accessed September 30th 2014.

Edward Nangle, The Achill Mission and the Present State of Protestantism in Ireland, Protestant Association, 1840.

Raphaël Neuville, “Les ors surréalistes de la monnaie gauloise”, Les Cahiers de Framespa, Issue 15, 2014, available at http://framespa.revues.org/2827, accessed October 8th 2014.

Henry Seddall, Edward Nangle, The Apostle of Achill, A Memoir and A History, Hatchards, 1884.

Barry Sheppard, “The Kirkintilloch Tragedy, 1937”, available at http://www.theirishstory.com/2012/09/24/the-kirkintilloch-tragedy-1937, accessed October 5th 2014.

Robin Chapman Stacey, Dark Speech: The Performance of Law in Early Ireland, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007.

JM Synge, The Aran Islands, Maunsel and Company, 1907.

“The Achill Tragedies”, available at http://www.askaboutireland.ie/reading-room/environment-geography/transport/transport-infrastructure-/railways/the-achill-tragedies/, accessed September 30th 2014.