Andrew Hunt

Andrew Hunt (1860-1946) was a hedge-school teacher, occult adept, and music-maker whose practical knowledge of bardic, folklore, and mystery traditions and his connections to contemporary art in the late 19th and early 20th century led to the creation of a body of avant-garde music, written materials, and treatises.

Hunt was born in Shanwallagh, Mayo to Bridget and Patrick Hunt in 1860. His mother’s family were well-known as musicians and teachers while his father’s family had resided in the east Mayo area for several generations. Thus, the Hunt family’s well-known associations with folklore, music, and scholarship would provide the young man with a plethora of knowledge from which a singular and inimitably Irish avant-garde art emerged. In time, Hunt naturally became a musician and teacher, the latter role giving him access to an oral tradition that encompassed bardic knowledge, in addition to the curriculum of the hedge schools where he taught.[1] Crucially, the prodigious Hunt also began to corresponded with like-minded individuals from his late teens, a habit he maintained throughout his life, and from the age of nineteen he would travel the North-Western region of Ireland teaching fiddle, flute, and voice in the Irish traditional style.[2] Indeed, one notable account of the young master depicts him as ‘handsome, brightly dressed with his gaze skyward, and the blackthorn stick over his shoulder with the satchel hanging from it’.[3]

It was during the last decade of the nineteenth century that Hunt came into close contact and correspondence with members of the secret societies An Druidh Uileach Braithreachas[4] and the Hermetic Society of Dublin, the latter formed by William Butler Yeats in 1886. These developments would shape Hunt’s life and art significantly as it was through these contacts that he would converse and engage with like-minded individuals further afield, in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States of America. Furthermore, Hunt was intimately familiar with fin de siècle European music: amongst his possessions are numerous such musical scores, the earliest of which is Trois Sonneries de la Rose+Croix, a rare Erik Satie score dating from 1892.

It was during the 1890s that the first written evidence of Hunt’s unique approach to music-making is evidenced, via his correspondences, diaries, and most obviously, in the document known as Automatic Music-Making (1893).[5] This latter two-page document, present in several private collections, was written by Hunt using the pen-name ‘Bráthair Aisling Gheal’, perhaps as part of his identity within a larger organisation or in an effort to protect his name.[6] Nonetheless, whether Hunt was operating alone in creating the material for these ‘knowledge lectures’[7] or with a group of associates known as ‘The Four Masters’, he brought forth an art that fused elements of the Hermetic tradition of Pythagorean music[8] with then current movements in contemporary European art, a project that would lay the foundation for future developments in the avant-garde.

Automatic Music Making – Andrew Hunt

The written directions for Automatic Music-Making bears witness to the creation of a ritualistic music, fully improvised, for one or more musicians using whatever instruments they see fit. Crucially, the openness to the world of sound espoused by Hunt allowed ‘nonmusical’ sounds to be introduced into musical practice:

All is vibration and light in Life’s infinite ocean of energy, thus, every sound is inherently sacred. Accordingly, when performing this automatic music-making, be courageous and daring enough to venture far beyond the beyond into the Great Unknown, yet remaining always in the here and now.[9]

Within the wider context of the Irish avant-garde, the music of female composer Billie Hennessy (1882-1929) would employ similar compositional approaches to Hunt’s automatic music, albeit her idiosyncratic use of such strategies led to the creation of non-improvised, automatic compositions that often extended for an hour or more.[10] As documented in the artist’s own extensive personal diaries, Hunt certainly had an awareness and appreciation for Hennessy and her music as one entry acknowledges her as a ‘True Gnosister of the Art’.[11]

Significantly, Hunt’s private correspondence reveals the extent to which he engaged with avant-garde artists during the twentieth century. His love of the French Symbolists [12] led to an invitation to visit Marcel Duchamp — the ‘modern alchemist artist’[13] – at his Puteaux home in the period prior to the outbreak of World War I. Here, among the company of Sonia Delaunay, Juan Gris, Fernand Leger, and Francis Picabia, Hunt discussed the Golden Ratio, Orphism, and the role of art in relation to the Spirit. Subsequently, on his return to Ireland, Hunt would explore the issues discussed on his visit to the Parisian suburbs, and in a letter expressing his gratitude to Duchamp, he noted ‘the need for new forms of representation to express that which is inexpressable, a post-symbolist art for [Hunt quoting Kandinsky] “the great epoch of the Spiritual [….] had already begun yesterday”.[14] Thus, Hunt’s engagement with his peers detail an artist who relentlessly sought to perfect his art, seeking a myriad of methods by which to transform consciousness through the creation of art and by the art itself.[15]

Significantly, Hunt’s private correspondence reveals the extent to which he engaged with avant-garde artists during the twentieth century. His love of the French Symbolists [12] led to an invitation to visit Marcel Duchamp — the ‘modern alchemist artist’[13] – at his Puteaux home in the period prior to the outbreak of World War I. Here, among the company of Sonia Delaunay, Juan Gris, Fernand Leger, and Francis Picabia, Hunt discussed the Golden Ratio, Orphism, and the role of art in relation to the Spirit. Subsequently, on his return to Ireland, Hunt would explore the issues discussed on his visit to the Parisian suburbs, and in a letter expressing his gratitude to Duchamp, he noted ‘the need for new forms of representation to express that which is inexpressable, a post-symbolist art for [Hunt quoting Kandinsky] “the great epoch of the Spiritual [….] had already begun yesterday”.[14] Thus, Hunt’s engagement with his peers detail an artist who relentlessly sought to perfect his art, seeking a myriad of methods by which to transform consciousness through the creation of art and by the art itself.[15]

Another excellent source of documentary evidence that demonstrates the influence of Hunt’s music and the ‘pioneering Spirit’[16] therein is to be found in the correspondence of American composer Henry Cowell and Irish poet John Varian between 1917-1918. Both Cowell and Varian had taken to study Irish mythology and folklore during this time, and it is apparent that fellow Theosophists brought the work of the redoubtable Hunt to their attention. Furthermore, Cowell had obtained a typed copy of Automatic Music-Making along with other of Hunt’s music, including Poem for Kettle, Mantel, and Table (1918), and the proto-Fluxus-minimalist work Whhhssst! (1931).[17] This latter piece comprised a set of performance directions that instruct the solo vocal performer to ‘extemporise a one-note hieratic vocalisation interspersed with long periods of silence using the word ‘Whhhssst’’.[18]

In addition to musical scores and written directions, Hunt also wrote a treatise on sound-colour corelation that built upon theories of his contemporaries Paul Foster Case and Edward D. Maryon. In particular, Hunt’s insights into the magical properties of sound and its relation to spiritual traditions — most especially in healing, ritual, and transforming consciousness are outlined. As further examples of Hunt’s written music and treatises come to light, documents uncovered during the course of this research suggest that recordings of his oeuvre may exist also.[19]

In his latter works from 1930-1944, Hunt applied the knowledge of the power of sound in conjunction with Pythagorean tunings, improvised sean-nós singing in a florid Connaught style, and aleatory procedures. Now, Here (1939) best exemplifies the combination of these diverse compositional approaches with instrumentation that included three gramophones, three radios, and three typewriters. This piece, the last documented music by Hunt, is a fitting finale for an artist whose music connected archaic traditions with the vanguard of contemporary art.

Notes

[1] As Yolanda Fernández-Suárez documents, hedge schools were in operation in Ireland as late as 1892. For more, see ‘An Essential Picture in a Sketch-Book of Ireland: The Last Hedge Schools’, Estudios Irlandeses, Number 1, 2006, pp. 45-57.

[2] Hunt’s granddaughter Mary Robinson recalls an early childhood memory from around 1944: “when [Hunt would] visit her parent’s home I’d often awake to hear a haunting, beautiful piece of music on the piano in the house’ (correspondence with author, July 2014).

[3] George Moore, diary entry dated 17 May 1881 (courtesy of Moore’s estate). Moore’s connection with the French art world and in particular the Symbolists, would prove crucial for Hunt as their friendship developed. In addition, Moore’s subsequent move to London in 1890 would pave the way for Hunt’s engagement with artistic circles there and in Paris, where Moore was close to a great number of prominent European artists, thinkers, and writers.

[4] This organization has documented roots that can be traced back to 1717. Furthermore, the Druid groves involved with the historic merging of 1717 can be traced further back in time to the tenth century when Haymo of Faversham laid the foundations of the Order; after Haymo’s death, Philip Brydodd would establish Mount Haemus Grove, Oxford in 1245.

[5] Hunt’s directions for this piece is included with this article.

[6] The music analysed in the course of this research, along with several other key written surviving documents of Hunt’s own art, are sourced from materials provided by his family’s estate, private collections, and his correspondences with others. Increasingly, items relating to Hunt are coming to light as scholarly interest in early Irish avant-garde art continues to develop.

[7] Automatic Music-Making first appears in the privately published Knowledge Papers, Course C, Lesson 19, 1893.

[8] As Joscelyn Godwin notes ‘the two great insights that emerged from the Pythagorean school are, first, that the cosmos is founded on number, and second, that music has an effect on the body and soul’. (Godwin, ‘Music and the Hermetic Tradition’, in van den Broek & Hanegraaff (editors), Gnosis and Hermeticism: from Antiquity to Modern Times, New York: SUNY Press, p.183, 2003).

[9] Andrew Hunt, Automatic Music-Making, written instructions, 1, 1893.

[10] Erik Satie’s influence was another point of intersection between these two artists. As an artist who functioned on the fringes of a largely indifferent society, Satie’s music and resolute individualism was a great inspiration to both: Hennessy’s Dada’s Mama (1917) and Hunt’s Poem for Kettle, Mantel, and Table (1918) were inspired by Satie, with the latter piece dedicated: ‘To the great phonometrician of Paris’ (Satie had declared himself to be a phonometrician, ‘he who measures sound’ in 1912).

[11] Andrew Hunt quoted in his artist’s diary, 8 November 1919, courtesy of the Hunt family estate.

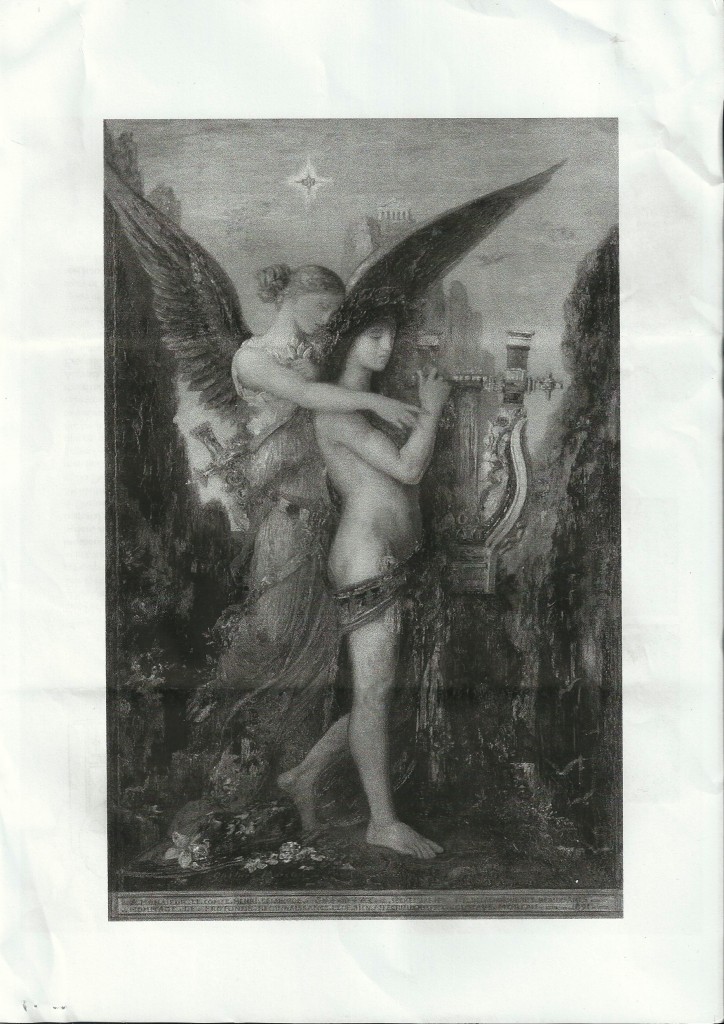

[12] For example, Hunt used a monochrome reproduction of Gustave Courbet’s Hesiod and the Muse (1891) for the purpose of providing the participant or participants with a magical image in Automatic Music-Making (see main illustration with this article).

[13] For more, see John F. Mofitt, Alchemist of the Avant Garde: The Case of Marcel Duchamp, New York: SUNY Press, 2003.

[14] Hunt, letter to Duchamp, dated 2 January 1914.

[15] As such, Duchamp’s own exploration of alchemical, magical, and mesmeric techniques may be viewed in a new light, and as Professor John F. Mofitt notes regarding techniques such as mesmerism ‘in its strictly artistic applications, its corollary became “automatism,” a somnambulist tactic producing the Duchampian procedure of an “art made by chance”. (John F. Mofitt, Alchemist of the Avant Garde: The Case of Marcel Duchamp, New York: SUNY Press, 2003, p. 28).

[16] Henry Cowell quoted in a letter to John Varian dated 17 September 1917.

[17] In 1933, Cowell tutored John Cage, an artist whose meditative and open-ended approach to sound was foreshadowed by Hunt’s pieces, most especially Whhhssst!

[18] Andrew Hunt, written directions for Whhhssst!, 1931.

[19] These recordings, reportedly made between 1929-1931, may yet prove to be among the earliest recorded documents of Irish avant-garde art. However, the private estate holding Hunt’s recorded music is not willing to make these documents available at present.