A Brief Introduction to the Guinness Dadaists

Ireland was an extremely chaotic place to live throughout the teens and 1920s. Ireland was one of the poorest countries in Europe, with over half of Dubliners living in appalling slum conditions. Coupled with this poverty the Irish were engaged in two wars – fighting World War 1, and a civil war against the British, who still occupied and ruled Ireland until 1922.

The art scene in Ireland was split between conservative painters such as William Orpen and Sean Keating, who painted in a traditional style using Irish folk scenes as subject matter, and more modern painters such as Mainie Jellett, who were interested in modern techniques such as abstract painting, and very sensitive to developments in art on the Continent. This split was again mirrored in literature – the nostalgic folk leanings of WB Yeats and his fellow Celtic revivalists were set against modernist experimental advocates such as James Joyce.

Despite their differences, all these artists were dealing with how to negotiate one’s identity and nationality. Dada in Ireland emerged as a product of and a reaction to these different senses of national identity. Indeed, it can be viewed as a synthesis of these polarities.

The Irish Dadaists are often called the “Guinness” Dadaists because the three most active members of the group worked at the Guinness brewery. This was important, because unlike the other prominent artists and writers of the time, the Guinness Dadaists were working class. Guinness was a remarkably progressive employer – it was one of the few places they could have worked and actually had time to make art.

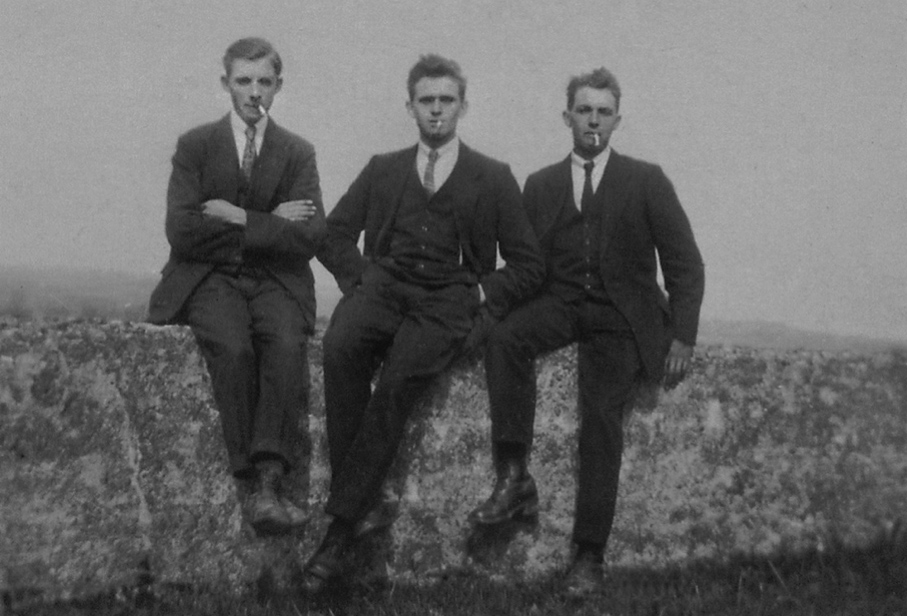

The three main protagonists of the group were Dermot O’Reilly, Kevin Leeson (seen above in the middle and on the right), and Brian Sheridan. The group was most active from ca. 1920 through 1922. Led by O’Reilly, the group put on performances, wrote sound poetry, and produced drawings and sculptures.

The Guinness Dadaists were pacifists where World War 1 was concerned, but not with regard to Irish civil war, with Brian Sheridan a proud member of the old IRA. (The term “Old IRA” is used to distinguish between the IRA who fought for independence in the Civil War, and the terrorist force of the same name.) The participation of members of the Guinness Dadaists in conflict set them apart from all other Dadaists, and may have been reason they were disconnected from other Dadaist groups.

What we do know of the Guinness Dadaists’ activities comes from O’Reilly’s notebooks and papers, held at Trinity College Dublin. These notebooks feature plans of performances, descriptions of sculptures made by Leeson and Sheridan, general notes and ideas. The entry dated April 12th 1921, for example, shows a rough plan for a wall hanging to be made by Leeson. Leeson was a cooper at Guinness, and the wall hanging was made from braces from barrels. O’Reilly describes in a later entry how he placed a pile of potatoes in front of the wall hanging, and stood on the potatoes to perform, wearing a green jacket which he had twisted out of shape with wire.

What we do know of the Guinness Dadaists’ activities comes from O’Reilly’s notebooks and papers, held at Trinity College Dublin. These notebooks feature plans of performances, descriptions of sculptures made by Leeson and Sheridan, general notes and ideas. The entry dated April 12th 1921, for example, shows a rough plan for a wall hanging to be made by Leeson. Leeson was a cooper at Guinness, and the wall hanging was made from braces from barrels. O’Reilly describes in a later entry how he placed a pile of potatoes in front of the wall hanging, and stood on the potatoes to perform, wearing a green jacket which he had twisted out of shape with wire.

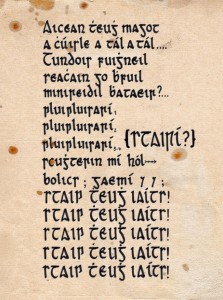

As well as the diaries, we have multiple examples of sound poetry written by the group. This is fortunate because very little of their drawings and sculptures survived the civil war. O’Reilly’s notebooks detail the different methods of declamation that were used. Some poems were designed to be performed simultaneously creating a cacophony of sound. Sheridan in particular was very interested in different types of chanting. Other poems were extremely rhythmic and percussive.

The Guinness Dadaists’ sound poetry is interesting because it is written mostly using the Irish alphabet, following Irish rules of pronunciation. Irish is one of the most difficult languages in the world to pronounce, and decoding the poetry for performance can only be done by Irish speakers. While the Guinness Dadaists’ choice to work with Irish was a political one, it was not nostalgic – it was not about looking to folk culture for a sense of identity. The Guinness Dadaists used Irish as a medium rather than a symbol, if anything they sought to weaponise it. O’Reilly wrote how:

The Guinness Dadaists’ sound poetry is interesting because it is written mostly using the Irish alphabet, following Irish rules of pronunciation. Irish is one of the most difficult languages in the world to pronounce, and decoding the poetry for performance can only be done by Irish speakers. While the Guinness Dadaists’ choice to work with Irish was a political one, it was not nostalgic – it was not about looking to folk culture for a sense of identity. The Guinness Dadaists used Irish as a medium rather than a symbol, if anything they sought to weaponise it. O’Reilly wrote how:

“…the Irish language is a material which can be broken into fragments which can be mobilised against all sense and meaning”

In this, they forged a completely new way of dealing not only with art and language, but also with nationality and identity.